Episode 7: Dan Yates, Opower

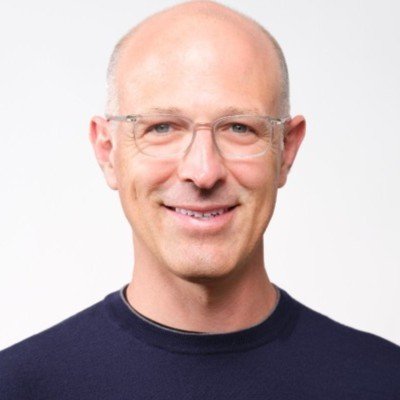

Today’s guest is Dan Yates, the Co-Founder and former CEO of Opower, an energy software company he took public and ultimately sold to Oracle for $532 million.

I was eager to speak with Dan, as he started Opower from a place of concern about the planet. It was clearly a financial win, but I had so many questions. Was it a win in terms of fulfilling the initial mission? How does he feel now about climate change vs when he started Opower in 2007? How is he evaluating what kinds of projects he takes on moving forward? What advice does he have for other people trying to figure out the same thing?

Dan is a consummate professional and clearly a great leader. I also found him to be quite humble and introspective. His perspective was quite helpful to me as I am figuring out my next moves as it relates to helping with climate change, and I hope you find it helpful as well.

Enjoy the show!

You can find me on Twitter @jjacobs22 (me), @mcjpod (podcast) or @mcjcollective (company). You can reach us via email at info@mcjcollective.com, where we encourage you to share your feedback on episodes and suggestions for future topics or guests.

-

Jason Jacobs: Hello, everyone. This is Jason Jacobs, and welcome to my climate journey. This show follows my journey to interview a wide range of guests to better understand and make sense of the formidable problem of climate change and try to figure out how people like you and I can help.

Jason Jacobs: Hello everyone. Jason here. Today's guest is Dan Yates, the cofounder and former CEO of Opower. Opower is the global leader in cloud-based software for the utility industry. Dan and his cofounder Alex Laskey founded the company back in 2007, scaled it over almost a decade, took it public until it was ultimately acquired by Oracle Corporation back in 2016.

Jason Jacobs: We talked about a number of things in this episode, including the initial motivation for starting Opower in the first place. Talked about, with the benefit of hindsight, whether Dan would call Opower a success. We know it was a financial success, but whether it was a success in terms of its impact on climate change. We talked about doing business with utilities and enabling the big incumbents to evolve versus the disruption path. We also talked about how that experience has informed how Dan thinks about solutions to climate change going forward. And finally, we talked about what that means for you and I and other people who might be also concerned about climate change and wanting to play a role to help. Took us a couple of false starts, but we finally ended up with what I think was a pretty good episode. So without further adieu, here's Dan.

Jason Jacobs: Welcome to the show.

Dan Yates: Great to be here, Jason.

Jason Jacobs: I have to tell you, Dan, I ran a venture-backed company over a number of years. We had a near-death experience. We had to cut a third of the team. We finally got back to our scrappy roots, and then we ultimately were acquired. And that almost killed me, but it wasn't nearly as stressful as trying to get this episode recorded with you.

Dan Yates: It warms me to hear that I am continuing to help you push yourself to new heights, Jason.

Jason Jacobs: But in all seriousness, I'm very excited to have you on the show. I've been long an admirer, and I'm grateful that you made the time to speak with me a few months back. And I've found your insights super helpful as I've been trying to make the transition into the climate fight. And I think you've got a great story to tell that can be quite beneficial to anybody who's looking to go through a similar transition, so I'm very glad you're here.

Dan Yates: Well thanks for having me. It's been fun getting to know you better over the last few months, and I'm really glad that you reached out when you did. And I feel like I've benefited a lot as well, so happy to be here, excited to talk about the climate and my experiences.

Jason Jacobs: Well why don't we jump into it. I mean, Opower, I'm sure a bunch of people know from a distance, one of the biggest energy software outcomes I think in history. But it would be fascinating just to learn more about how Opower came about. What inspired you to start the company?

Dan Yates: I'd started a software company before. A friend of mine and I, right after college, about after college, decided to start a business. We'd started an educational software company, and it was really valuable, and it was meaningful to me to start a business that had a mission as well as a good financial idea. It's just so all-consuming to run a company that I felt if I was going to orient my life in that way, where almost everything I was doing was for the business, that I needed to care about it more than just making money. That's how I'm wired.

Dan Yates: After I sold that company in my mid-20s, I took off about a year and traveled with my girlfriend at the time, who's now my wife, so it was by any measure an excellent trip. And we drove the whole Pan-American Highway, and we bought a used Toyota Fortuner, shipped it up to Alaska, and drove from the Arctic Sea down to Tierra del Fuego. We had a great time, and there was no mission, so to speak, on that trip. We just wanted to have an adventure.

Dan Yates: But what it turned me into in the process was an environmentalist. We listened to Jared Diamond's book Collapse on iPod as we drove south. And we just witnessed personally the amount of degradation everywhere. I think I left on that trip with a mental model that the US was degraded and other countries were still wild untouched, and for the most part it's actually the opposite. US and Canada are some of the most untouched, pristine landscapes still left on the planet, and everywhere else has been even further degraded.

Dan Yates: And I came back really galvanized to do something. And when we moved back to US, started looking around, and I started to search initially very, very broadly, in a similar way to the kind of I think the questions that you've been asking and that you'll continue to ask on this podcast. For me, part of that search was actually a moral search to convince myself that I could move away from education and essentially the impoverished youth globally and in the US to have better opportunity to the environment. I actually read a bunch of environmental ethics books, the topic of which is beyond the scope of this hour, but in fact it was important tome and it helped me get certainty and confidence this was the direction I wanted to dedicate myself in.

Dan Yates: And then I made two important narrowing decisions. One was, I realized a lot of you work on [inaudible 00:05:31] the environment, but if you're in the US, the thing we do really poorly is emissions. So I decided to focus on that. And if you worry about things like habitat protection and really equally important problems, you really should it in other countries first in foremost, because that's where the biggest battle is fought. I was potentially ready to move. My wife wasn't. And that was that.

Dan Yates: Secondly, and this is, I think, a general rule also for folks thinking about making a move towards climate-related issues, is a realized that the best thing for me to do was to not throw away the last almost 10 years of work building fast-growth software startups but instead to try and stand on it. So I decided to look within where I had already amassed skill and a reputation and say, "What can I do using those capabilities?"

Dan Yates: And then there was some just good luck. I had this idea out of the blue. It didn't seem like a business idea. It didn't even seem like that great of an idea. But I was living in San Francisco at the time. I was PG&E customer. And [inaudible 00:06:28] I had the good fortune that PG&E at the time had one of the worst utility bills in the world and in history. They had an antiquated system that couldn't actually bill you across months. And since you're meter wasn't always read on the first of the month, if the bill went across months, you actually got two half bills, and you had to add it up yourself. It was staggering. It looked like it came off of a 1980s dot matrix printer.

Dan Yates: And I'm looking at this thing in between reading my environmental ethics books, and I'm thinking, "What a huge missed opportunity." You do the easy math of 100,000,000 homes in the US, and there's like over a billion of these bills going out a year. I was thinking, "This should be the marketing channel to help educate people about energy and energy efficiency, and I can't even figure out how much I owe, let alone learn why I used what I used."

Dan Yates: And I had this very simple, naïve idea of, "Well, look. I don't know what a kilowatt hour is, or a megadekatherm. Can you just tell me how my energy use compares to similar homes in the area?" And I was mentioning this to another person working in this space. It was actually the [inaudible 00:07:30] Foundation at the time. And her eyes went wide and said, "You can't believe this, but we actually just funded a behavioral scientist who did research on essentially exactly this and proved that it really gets people to reduce usage." So she went back to her office. She scanned the... This was like 2007. People were still scanning and PDFing things around. She canned the result in a PDF, emailed it to me. And this professor, Robert Cialdini, had literally just demonstrated in Southern California that if you show people their energy use compared to their neighbors, that on average he was getting a 6% of energy use across the summer in this small test.

Dan Yates: My cofounder and I at the time, we were exploring a bunch of ideas, with Alex Laskey, he and I ended up cofounding Opower together, our eyes went wide reading this data. And we had figured out that there was these funding streams coming from state regulations that were driving utilities to run efficiency, and they worked on this basic math of essentially a cost-effectiveness analysis. If you could do something that led to a certain amount of savings, you'd calculate the dollars you spent to do it divided by the savings, and you'd get a cost per kilowatt hour. And if it was really cheap enough, then it would qualify for this funding. And all of the other programs were basically subsidizing products. So when you go buy an LED in Massachusetts today, an LED light bulb, it's actually cost a lot more than what you paid, because the State of Massachusetts runs a huge program that subsidizes those bulbs because they save a ton of energy and it makes sense.

Dan Yates: So we [inaudible 00:08:59] and we thought, "Geeze, if we could save even a percent, instead of 6%, by sending out communications to customers, this would be a cost effective efficiency program." But it wouldn't be a product. It wouldn't be a an installed thing, or as the industry calls it an installed measure. We didn't know what it would be named. There wasn't a name for it.

Dan Yates: So went out to Arizona State where Professor Cialdini was, pitched him on the idea. He loved it, because he loved the idea of some young entrepreneurs try to commercialize some of his research, because that's the ultimate proof that he's on to something. He joined us as an advisor. We raised a round of funding. And then we went out to sell some utilities. That was the biggest challenge to us, were two questions, with one, will any utility ever do this? Because it was risky and different and weird, and they don't really have a strong incentive to do anything that fits into any of those categories. And two, will it actually work? Professor Cialdini had done this test, but it was only 300 homes, and it was three months, and we needed this thing to go across 30,000 home for three years.

Dan Yates: And my cofounder Alex was the world's greatest and most lovable salesman and just an amazing momentum builder. Within a few months had gotten us in a place with a utility which had some enterprising and pioneering folks, a utility in Sacramento. They took the risk on us. They signed a first contract. And we were off to the races. And we ran the program, and it worked. Over the lifetime of the program, it was like a one-year pilot, we got I think a 3% reduction in energy consumption. It was very cost-effective. And we were off to the races. That was when the company really started.

Dan Yates: Then we ramped up, and we hired more people. And then we were on essentially an eight-year journey of convincing every utility across the country and every regulator that this new category of efficiency program, which over time became named behavioral efficiency, was appropriate and credible and that it actually was long-lasting, should be a part of energy efficiency portfolio that these states were demanding from their utilities. And then as the company grew and grew, we added on new products. We ended up taking it public in 2014. And then two years later we got acquired by Oracle.

Dan Yates: That last five sentences made it sound like it was just one smooth, celebratory up and to the right. While probably don't need to go into this for this podcast, I can assure every listener that on the inside, it was everything you described your journey at Runkeeper to be. It was high stress. There were up and downs, and there was panic, and there was moments of victory but they were very brief in between long stretches of uncertainty and everything in between.

Jason Jacobs: Thank you for that, Dan. A couple things I want to dig into based on what you just went through. It'd be great to talk a little bit about energy efficiency and how that fits into the climate fight, how impactful it can be. And then secondarily, I'm really interested, because energy efficiency, whether it's a little impactful or a lot impactful, it's a net good for the cause, but I'm curious just what mobilized the utilities to act, since I have a feeling, and call me a cynic, that it wasn't just out of the noble concern for climate.

Dan Yates: Energy efficiency... It's funny. It's like the least-sung hero of the climate fight. So first of all, what is energy efficiency? Energy efficiency is just any project, product, process that allows you to deliver whatever business or use outcome you're looking for with less energy. So whether it's an LED light bulb, or Opower's behavioral efficiency program, or even process and system optimizations at manufacturing plants, these things can all qualify as efficiency, because at the end of the day you get what you wanted. Nobody actually wants to use energy, is kind of a key basic insight. You want outcomes from the energy. You want light. You want [inaudible 00:12:53]. You want an iPhone. You don't want it to consume energy. So efficiency is just anything that gets you what you want with less energy than what had been there before.

Dan Yates: And the fact is that if you look at what the international association of scientists who publish the plans on how we possibly might be able to avoid [inaudible 00:13:12] confidence but some fraction of the climate catastrophe that we're facing, still the largest wedge is energy efficiency, because it is sort of other... If all of the resource or supply, the energy generation, is one side of the equation, the entire other side of the equation is the demand and the consumption. And there just remains huge uncaptured opportunities to further drive down energy consumption through energy efficiency.

Dan Yates: So it doesn't get the attention it deserves, but it is actually... It's massive. And in fact, the way I ended up thinking down this path in the first place when we started Opower was to ask some of these basic, fundamental questions of where can I have the biggest impact. I downloaded this map of energy usage in the US from the Energy Information Agency, the eia.gov. And it had this sort of awkward-looking picture of all these flows coming in from the left and then consumption categories coming out on the right. And I realized that everyone I was talking to was only focused on technology on the left, and no one was focused on the right. Nobody in Silicon Valley was thinking about efficiency. Everybody was thinking about wind and solar and biofuels. That's actually how I got oriented first starting to think about things like energy information and helping people to save. It's massive, and it's underattended.

Jason Jacobs: Before we get to the second part of that question, in terms of what motivated the utilities, one thing that I'm [inaudible 00:14:37] as it relates to this energy efficiency is, as it's been explained to me, with the caveat that I'm only a few months into this journey, I'm flat-footed, so I'm learning just like a lot of our listeners are, but the way it's explained to me is, we have this carbon budget. And the carbon that we put up into the atmosphere is there for hundreds of years, meaning that whatever we put up there now, or even what we've put up there over the last several decades even, it's going to be there essentially for as far as the eye can see. So when it comes to emitting less... Emit 80% less. That sounds like a big number, and a lot of us would be high-fiving because we reduced 80% of emissions. But the fact is, we're still emitting 20%, which still increases the carbon that's in the atmosphere year over year and makes the problem worse. So really we need to get to zero carbon energy sources, and [inaudible 00:15:32] pull a bunch out.

Jason Jacobs: And when you had talked about early on in the company it being very validating to run a test and find that you reduced energy consumption by 6%, to me that sounds small and inconsequential. So I'm just curious how you react to that, and whether you think about it as I have, or if there's an alternative perspective I should consider.

Dan Yates: I feel confident that we can't bet that there's going to be a single silver bullet that solves the problem. So I do think we should be working on some of the silver bullets. As much as it seems eternally 20 years away, I'm so happy there are some people doing fusion research with all their heart, because there would be nothing better than a radioactive-free, eternal and endlessly available supply of energy that has no emissions. So we should keep chasing that stuff. At the same time, we need to keep chasing lower risk approaches to getting where we need to get.

Dan Yates: And I think the thing to think about is, we already have a lot of ways to produce energy without any emissions. Let's just take solar and wind and large hydro. These are all good examples. The problem is that we don't have enough installed to meet all the demand. So if you reduce the demand... Let's say we reduce the demand by 5%. That doesn't have to cut emissions by 5%. That has to cut 5% of the emitting resources. So if you're in a place where you're at 50% renewable, I cut consumption by 5%, I can cut the emittive remaining portion by 10%. And then as you get further down the path, if I reduce demand by 20%, and I only have 40% of my stacks still emitting, then I've actually eliminated half of my emittive stack problem. Every time you cut a power plant's worth of consumption, it should be the most emittive, dirtiest plant that gets turned off. So that's how to think about demand reduction.

Dan Yates: The problem is, demand is actually going up right now. So people in the developed world, if they all had the same number of incandescent that we had 10, 15 years ago, we would be screwed. If they put in LEDs, the lighting problem is actually about a tenth as big of a problem as it used to be. So it's a really big deal that we have LEDs, and the fact that energy efficiency programs help to accelerate their market adoption is a really big deal.

Dan Yates: Specifically to Opower, the way I think about it is... I'm of two minds, to be frank. I've had some learning in the process. So on the one hand, I can't feel anything but unequivocally really proud of what we did. As Opower grew and it runs today as a successful part of Oracle, we save every year functionally about the same amount of energy as the Hoover Dam puts out every. The Hoover Dam is one of the largest public works projects of the 20th century in the US, and we've generated a Hoover Dam's worth of energy, of zero emissions energy, without having to build the largest dam in America, and we've done it in a shorter timeframe. That's awesome.

Dan Yates: Now at the same time, any listener would agree that no one in the last year has said, "Well, I was worried about the climate, but thanks to Opower, it's not an issue anymore." We didn't fundamentally change the course of history. But I don't think anyone will. Any one group or person wont'. We need millions of people working on this problem and in lots of different ways. Son that context, I can be proud that I've done my part, and I'm still here to do more. I think that's the right mindset.

Jason Jacobs: So you've talked about kind of the mission-driven founding story, and kind of that mission is the engine that enabled you to power through the ups and the downs along the way. And you've also talked about impact and how to think about efficiency and demand reduction as part of that equation. And I think that makes sense, what you said, about how it's only one part and it's not a silver bullet but it's one thing we can do to help alleviate some of the pressure as we're continuing to attack the problem from other sides as well and kind of judo it.

Jason Jacobs: I guess the one thing that we didn't cover yet that I don't want to lose is just, now let's come back around to our friends the utilities, which were your core customer base, which many in the climate fight look at, rightly or wrongly, as the enemy of sorts. Is that distinction justified? And what was it, do you think, that mobilized them, since I imagine it wasn't the same mission-driven purpose that you were describing for Opower?

Dan Yates: Utilities are not immoral. They are, like all profit-seeking enterprises, amoral, and I think that's something that we struggle with or fool ourselves sometimes about in capitalism. The capitalist construct does not reward morality. It rewards survival and growth.

Jason Jacobs: Evan, we should keep that quote right there. Keep going. That was a nice little soundbite.

Dan Yates: Thank you. And now that my train is broken, we'll just go back to my normal, plodding sentences. But sincerely, right? There's real, sincere effort to try and change that with B Corps, and I'm of mixed opinion on that, and let's not spend time on the nuances of B Corp and whether it works or not. The problem is that the massive centerpiece of our society is capitalist and it's amoral.

Dan Yates: So the utilities are amoral. The mental model needs to not be on our side or against us. It's incumbent and disruptor. Our mindset at Opower was... It had to be, because of the approach that we took. We were disruptive within the energy efficiency program ecosystem, but that ecosystem was managed and maintained by incumbents, the utilities, so we had to work with them. And we did, and we came to actually really know and like... Not actually that it's so surprising, but over the course of my last 10 plus years in industry, I've come to know and become friends with many people who work in utilities across the country, and they're people, and they're hard-working, and they're smart, and they have a very hard job, because they're not always loved.

Dan Yates: The CEO of the utility in the '50s was a star of the community. He brought light and heat and radio and television to every home in the area, and that was a point of great pride. And now they've been demonized as these evil emitters. And they're doing the same thing they were doing in the '50s, right? And they're just fighting for their return on investment.

Dan Yates: So that's sort of how I think about utilities. The critical thing, of course, is that's not sufficient for them to somehow get into this business of helping people use less of their core product. That's very counterintuitive, doesn't really make any sense at all. And the answer there simply is regulation. So there's some very smart environmentalists in the '80s in California started a project to pitch what they called a megawatt, which was to say that the least emittive watt consumed is the one that you never do consume. And so let's stop only focusing on renewables and try and focus on, essentially, energy avoidance, before it became energy efficiency.

Jason Jacobs: Like Jimmy Carter, wear your sweater?

Dan Yates: Yes. Precisely. So these laws were passed, and they put a tax on the utility bill that funded efficiency programming in California. And then there's been a back and forth over the last 40 years as these things... whether or not the utilities should run the program or somebody else. And over time, everyone's converged that it's so entwined with the utility business and the utility is already so regulated that in fact the utility is the right place to locate the programs, but that has been, frankly, a policy decision, not a necessity. Consequently, what you have are these captive funds of hundreds and millions of dollars, and in California's case billions per year that are spent to help drive efficiency in the states. And then the utilities have to spend that money, and they have to spend it exclusively on efficiency programs. So then what you're really doing is competing the alternative efficiency programs like light bulb subsidies and air conditioner rebates and what have you. So that had to exist. That was the policy that marketing identified and targeted and went after as Opower, and we wouldn't have been able to pursue the business model that we pursued without it.

Jason Jacobs: And that would be-

Dan Yates: As a word of caution to any listener, do not go with a green-friendly product selling to utilities unless there's some regulated funding stream that's going to pay for it, because they're self-interested, not green-interested. That said, increasingly those two things are becoming one and the same, because the regulators, especially in coastal states or progressive states, are so primarily focused on emissions because they don't have huge capacity or infrastructure problems. The carbon footprint or carbon emissions profile of the state is becoming the dominant... in most become the dominant issue, and so every negotiation the utility goes through with their regulator is going to involve emissions at some level.

Jason Jacobs: Hearing this, that leads me to a couple of follow-up questions, or really it's the same question through two different lenses, which is, if you were going to start another clean energy software company today, since we just discussed how financials and mission are distinct things that sometimes overlap on the Venn diagram and sometimes do not, if you were looking purely with a financial lens, is it better suited to be an enabler of the incumbent or a disruptor? And then I would ask you that same question with a mission hat on.

Dan Yates: I have seen a lot of interesting enabling technologies and disruptive technologies. And the analogy I think of is kind of like somebody asking, "Is it better to be an enterprise software or consumer software?" It's like, well, on the one hand, the four largest tech companies are mostly consumer, so maybe that's the right answer. But there's some pretty darn big enterprise software companies too, so it's hard to say that you can only make money on the consumer side. And even some of the most consumer-y companies like Amazon are actually making almost all of their profit from the one enterprise side of their business, which is AWS. It's very equivalent here. If you're building large-scale power generation, you're customer's eventually going to be the utility or a merchant generator. At the same time, it's hard to look at Tesla and not say that disruption isn't a great way to go.

Dan Yates: So I'd almost feel like, to me... And this is something that I've come to think is actually the right answer in a lot of these domains. The question turns to, what do you like? What's your personality trait? Do you like to be an insurgent who breaks out from the pack and has total control of their own destiny and kind of lone wolfs it a la Steve Jobs? Or are you someone who is more of a networking collaborator who likes to be an enabler, to use the exact word, and enjoys working with other people in industry to help pull on one our on a very large ship? And it's kind of like personality traits that drive you to the kind of products and solutions that you enjoy building.

Jason Jacobs: So what if what I like is keeping the planet sustainable for humans and other lifeforms for as long as we can in as a healthy a way as we can for life as we know it? Do we work to enable the incumbents to adapt? Or do we burn them down?

Dan Yates: There's no world I see where we burn down all the incumbents as the fastest way forward. And I think like, what's been the most rapidly adopted renewable energy methodology in the last 40 years? It's wind. And all of the wind that's going in... I know it's sort of funny that 90% of the wind that will go in, and I'm just making up that number because I'm confident that it's at least that, is going in from big incumbents, because they are the ones that have access to very low-cost capital and can bankroll billions of dollars of infrastructure build.

Dan Yates: Now, how many of the utilities invented new, more refined wind turbine designs? Zero. How much of the really advanced wind turbine design even came from big, industrial incumbents like GE? I don't know for a fact, but I'm sure the minority of it came from them too. I'm sure they were scooping up startups left, right, and center. But the fact is that the big guys who build most of the wind, both turbine and then actually buy and install them, those are all incumbents that have been around forever.

Dan Yates: I think it's hard sometimes folks to realize how big the energy industry. The utility industry alone is a $2,000,000,000,000 global industry. You think about the things we've done in modern living, energy and electricity generation is easily in the top five, 10 list of global historical accomplishments. And commensurate with that, it's a huge share of wallet and of essentially what we do on this earth. Writing that whole group off is like a fool's errand.

Dan Yates: You can see already how the tipping has started to happen. You look at political alignment around things like extending the investment tax credit for wind and solar, a lot of the wind resources are in very red states like Texas. And Texas is very, very supportive of extending that tax credit now, which is a subsidy for renewables. And at the state level, the government is not doing those kinds of things, but they are very eager for the federal government to continue to subsidize wind, because now they're the incumbent. You have to get to that point to have political will to move these things.

Dan Yates: This battle is a battle of both political will and technology, and to me, technology... It's hand in hand. Political will helps to create subsidies and political policy actions that encourage technology development, and then technology development makes it cheaper to change your mind politically. And those things are a positive cycle, and you need both. And it's the exact same thing with incumbents and disruptors.

Jason Jacobs: It reminds me also of... I mean, there's like a chicken and egg on the consumer side too, because it's like, does consumer behavior change matter? Well, maybe consumer behavior change, if you just look at the data in a vacuum, it's not going to move the needle that impactfully, and the impactful stuff is going to come from, as you said, things like top-down regulation. But how do you get the right policies in place? Well, you get the right elected officials in office. How do you get the right elected officials in office? You get them voted in. How do you get them voted in? The consumers have to give a crap, right? Yeah, so how do you get them to give a crap? Well, you first awaken them. How do you awaken them? Well, you start getting them to pat attention at a small scale, right? And so it all comes back around.

Jason Jacobs: And to be honest, I'm still going through that tug-of-war, because I only want to work on impactful stuff, but it's like you also have to walk before you run, and those are difficult trade-offs to kind of sort your way through, I'm finding.

Dan Yates: It's a very important topology to assess of what's important and what isn't. But unfortunately, that topology doesn't fall into these sort of more shallow, neat categories of disrupt or enable and tech policy, because there are really important things in all four of those categories and quadrants. It's within each of them that you are like, "Well, that disruptive technology idea doesn't have legs for all these very particular, nuanced reasons. And this particular incumbent-influencing policy also doesn't have legs for these other totally different reasons. So don't waste your time on these two. But then here are two interesting disruptive technology and incumbent political ideas that are both super important. You should work on either of them."

Dan Yates: That's the challenge. Can't sort of summarize it in a... Well, I'm hopefully taking you another inch forward, but you need many more episodes, which it sounds like you have coming, to get to the final answer.

Jason Jacobs: Dan, if you give me an inch, then I'll take a mile. Switching gears for a minute, you talked about how basically it's like, we need it all, and we need more, and it's about each person kind of sorting through, and then within each area it can be an impactful area, but that doesn't mean that off-hand everything in that area will be impactful, and there's select things in each area that could be impactful. So it's less about the area and more about the specific thing within that area, and that each person needs to find their own strengths and marry those two.

Jason Jacobs: So here's a different question. If you had $100,000,000,000, right? Dollars don't have skillsets, right? And so dollars don't have passions. Those dollars can be allocated anywhere that you want. If you could allocate that either to one thing or across a portfolio of things to have the biggest impact on helping achieve the deep decarbonization that we desperately need, where does it go?

Dan Yates: I mean, that's a very deep question to ask. Not to flatter you in the sense of saying you're deep, to say the answer to that is a deep project.

Jason Jacobs: No, no, I heard that I'm deep.

Dan Yates: [crosstalk 00:32:29]

Jason Jacobs: And thank you for that [crosstalk 00:32:30]

Dan Yates: I don't know that I have a global answer for this. It's funny, because where my mind starts to immediately go is like, okay, $100,000,000,000. What category of activities does that give me? Is $100,000,000,000 enough to successfully effectuate the policy change of the cap and trade system in the US? I bet it isn't. $1,000,000,000,000 enough? Probably. If we had $1,000,000,000,000, we could probably over night pour in enough subsidies into the right domains, the right political states, senate offices, and congressional offices, and get cap and trade enacted. There's some number that's in that range that would make that happen. And I think that would be worth thinking about, because cap and trade then facilitates... Or carbon tax, to say it more plainly. Carbon tax is an invisible hand that then realigns the capitalist markets to pursue carbon reductive actions everywhere you look. And I think that would be very powerful.

Dan Yates: If I poured $100,000,000,000 or $1,000,000,000,000 further into R&D, I don't know. Some money should go into R&D for sure. I don't know how quickly we could absorb that money effectively, but there's some ramp that I would love to see where we poured 30% more a year over the next 10 years and then grew a really robust and attracted the best talent globally to work on these problems. That's definitely another dimension I would be very interested in.

Dan Yates: I wouldn't put it into venture capital, because we're flush with it, not because it's not important. We have enough. The other area that people talk a lot about is that there's this tweener problem with clean that it's hard to get traditional VC but you're not yet able to access more lower risk funding sources. I don't have a strong enough sense of exactly how much money is needed for that and how real that is, but I suspect that there is something there, and that would be another area I would look.

Jason Jacobs: Reflecting on what you just described, I think what I've heard from you over the course of this discussion is that, on the one hand... and actually from our discussions over the last few months as well. When you talk about yourself, I know I've heard you mention that you like to kind of get in when there's not a lot of science risk and you can really kind of swing a big bat with deployment. So that's how you think about kind of where your skillset is most impactful.

Jason Jacobs: At the same time, though, I think what I heard from you with this $100,000,000,000 question is that the policy side is really a big lever. And so selfishly, one question I have for you that I'm really interested in your answer on, because I'm [inaudible 00:35:12] with it a lot, is that you've got a skillset that is more on the innovation side where things are ready to rapidly scale, but you also have some flexibility in terms of how you spend your time, and you're deeply concerned about planet, and the regulatory side seems like it's going to move the needle more than anything else, so how do you reconcile those two things?

Dan Yates: I've struggled with this a lot. And what I've ultimately come back to is this totally banal bromide of follow your passion. And I think I kind of said it earlier, and I want to say it again and call out how hackneyed and overstated that phrase is. I keep coming back to it because it actually is what I keep finding governs me. And to be specific here, I don't get jazzed working on regulatory stuff. I'm in fact working on some regulatory stuff with the company, Dandelion geothermal, that I'm very, very involved with right now. And it's fun as a sidelight, but that's not how my mind works. Regulatory and policy stuff is the province of folks who are incredible at remembering all these different connections between people in a network, and recalling who knows who and how and what their motivations are, and having this kind of like superpower of mirror neuron capability, this is sort of theory of the mind capacity to map out everybody else's mind. And I honestly, I'm just not that good at that. It's enervating for me.

Dan Yates: On the other hand, I read a book with 10, 15 names and their roles, and you ask me a minute later what the names were, I never even processed it. In the same book, it has a system diagram of how a nuclear power plant operates, albeit a simple one, and I'll be able to describe to you a day later the different between a boiling water reactor and a pressurized water reactor.

Jason Jacobs: We might have to found a company together, because I swear I'm the exact opposite.

Dan Yates: This is profound stuff for people. Even if regulatory is the most important thing, I can't be the guy waving the flag at the front. I'm just not good at it. And I'm really in some other areas exceptional at stuff that has to do with planning and systematization and prioritization and diagnosis of problems and a lot of the stuff that shows up in early stage venture where it's as much about that stuff as it is about relationships. There's other things. I happen to be a good recruiter, which is essential to start a company. So I have a couple other skillsets that particularly drive me towards early stage companies, not just systematic thinking. And I think I can be persuasive one on one. But I'm bad at the body politic, and it's showed up-

Jason Jacobs: Charming, you tell the jokes [crosstalk 00:37:42]

Dan Yates: Certainly receptive to flattery, for what that gets me. But you know, I'm not alone on this. And I'd actually put up two people who we all look at titans of industry, period, as good examples of how we weave these larger than life narratives, but there's always these surprisingly convenient self-interest narratives that seem just as explanatory of the reality. And the two people I'd put up are Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk.

Dan Yates: So Jeff Bezos just did this big TED Talk-style announce basically of the lunar lander and revealed that they're going to the moon, and that's the whole point of Blue Origin. Did you happen to watch his hour-long speech?

Jason Jacobs: I didn't watch the speech, although I read an article talking about Blue Origin and how everything he's doing at Amazon is essentially the cash cow to fund Blue Origin.

Dan Yates: Yeah. He's selling a billion dollars of stock a year to fund it, so in that sense, yes, but I mean, they're obviously totally separate entities, and as rich as he is, he can do whatever he wants with a billion bucks a year.

Jason Jacobs: Which is still not policy stuff [crosstalk 00:38:42]

Dan Yates: So he went through this whole, what I felt like, tortured and ultimately not that credible argument of how... His strawman that he was fighting against was, "Why aren't you spending a billion dollars a year on climate change or poverty or refugee problems? There's so many other things. You're spending this money to go to the moon. Why are we doing this?" And he made this elaborate case of how if we don't leave the Earth, we will eventually run out of resources, and that will lead to stasis and rationing, and as a species we are driven by growth and dynamism, and this is a necessary path, and he wants to be part of the solution, to pave this sort of century- or millennia-long path into the interstellar great beyond for the future of humankind.

Jason Jacobs: He wants to go ruin the next planet after we already finish ruining this.

Dan Yates: Yeah. I mean, there's every argument to be made that no planets that we've ever seen are even a quadrillionth as complex as ours, so that's not really an issue, but yeah. He wants to go mine the moon instead of mine Australia, which I actually thing would be terrific. But [inaudible 00:39:49] let me just state my conclusion here, and then I'll just repeat it very quickly with Elon Musk. That sounds really noble, and it's kind of an elaborate tale, but there was another thing he did, which is he showed an article of when he was 18 or 16, interviewed in his high school town, the town he grew up in, in that local paper, talking about at 16 years old that he wanted to go to the moon, basically. He wanted to be part of the effort to build an interstellar future.

Dan Yates: So one narrative is, he has really thought super deeply about the future of mankind, and he's analyzed that there's a lot of money and attention on climate change, and a lot of money and attention on poverty, and not enough relatively allocated to space exploration, and so he's putting his money where the most optimal spot is for the future of humanity. And by the way, if you [inaudible 00:40:44] how could you possibly, incidentally, do some sort of rational, non-subjective calculus to come to the conclusion as to exactly how much should be allocated in either domain? I wouldn't know where to start. But let's assume that's even possible.

Dan Yates: There's an alternative analysis of just, he's a space nerd. He's always been a space nerd. It gets him up in the morning. He couldn't be more excited about it. And it's his money, and he's going to build a fricking spaceship to the moon if he can afford it, because nothing's cooler for him on Earth. And he's going to work day and night to do it, and he's going to be incredible at it, and it's going to happen. I'm pretty damn sure that the real story is the second story.

Dan Yates: And then you look at Elon Musk, and it's a similar thing. He has this 10-year, 20-year vision, which incidentally is a brilliant vision, for how to build a successful electric vehicle company. It's going to have a big impact on emissions. In the Elon Musk case, I honestly believe he is sincerely committed to the environment. But how did he pick to do electric vehicles? Is it a coincidence that the other things he's doing is building a spaceship and trying to dig massive tunnels through the earth? No. The guy loves physical infrastructure. He dreamed up a Hyperloop, yet another way to rapidly commute from one place to another. This is what his mind races on at night. I'm so thankful that he has dedicated his time to Tesla and is having a huge impact on the future of emissions in transport, but he's the right guy for that because he just fricking loves doing things like building spaceships and cars.

Dan Yates: To me, it's two stories, right? It's one story is amazing effort dedicating yourself to a mission bigger than you and putting it all into getting it done. And the other one is picking a way to do it that is easy for you to be passionate about because you want nothing more than to think about it anyway, and there's no difference between fun and work for you because it's actually where your passions are aligned.

Dan Yates: And that, I think, if I'm going to leave one message to this sort of strategic question of where you should be assigning yourself in this climate fight, that's the message. Find a way that you get motivated and can work day and night and know that you're being effective.

Dan Yates: And for me, like the analogous version here is I can't do projects that have like a 10-year lead time before I know if they work. I need to see immediate results in the here and now. And that was the case with Opower. We had an internal mission statement, "Save energy now." We were not trying to convince people to build some power plant in 10 years. We were sending out these communications that save energy tomorrow morning. That resonated with who I was and how we thought about things.

Dan Yates: And also the companies I'm getting involved with today, the one I'm most deeply involved with, as I mentioned, is Dandelion geothermal. It has an absolutely enormous potential. It could be a $50,000,000,000 company. It could be the future of how we heat our homes and cool our homes. But we're also selling and installing today, and we're saving energy every day, and that was really important to me, because it's not something I have to dedicate five years and wonder, "Is it going to get anywhere?" We're already getting somewhere.

Dan Yates: So that's something I know about me. So I know I'm not cut out for like deep academic research. And then I also, for the reason I described before, know that I'm not cut out for policy and politics. So thank God I am cut out for early stage startup stuff, because there's kind of nothing left. I also can tell you I'm terrible at having a boss. I wasn't good in corporate America either. So my options winnowed pretty quickly, and I frankly was just lucky to find out that the startup thing worked for me.

Jason Jacobs: I mean, you could be a podcast host if the startup thing doesn't work out going forward.

Jason Jacobs: Well, my last question was going to be, what do advice do you have for any listeners that are feeling like you and I are, where we've got this climate crisis hanging over our heads and not sure where to start or how to go about it? But to be honest, I feel like you just already nailed.

Dan Yates: Thanks. Yeah, that is my advice. I guess I would add, we don't have enough people doing it. So it's not a question that the people are doing the wrong things. It's just that we need more. There's important work to be done everywhere that I look.

Dan Yates: So Dandelion geothermal does electric-only, very efficient method to heat and cool homes. We need electric heat, because we need to move away from the combustion heater, just like we're moving away from the combustion engine in the car. Okay, that's one of 1000 things we need to do, though. We need different forms of energy generation. There's a coming wave of new nuclear technologies and more growing passion to review the decisions of 60 years ago to walk away from nuclear. We need people looking at that, and if they're believers championing it. We need more people working in energy efficiency. We need people working in policy and politics, working for these issues. We need people getting out the vote. I'm following a guy who runs a project called the environmental voter project, and one of the things he's discovered is [crosstalk 00:45:40]

Jason Jacobs: He's going to be a guest, actually. Nathaniel.

Dan Yates: Really? Great. And as you know, he's discovered that there are tons of environmental votes. They don't vote at the same frequency as the rest of us do, or [inaudible 00:45:49] the rest of your listeners don't vote for that exact reason. So we should say to everyone here listening to this, please go and make sure you vote in the next election.

Dan Yates: There's so many different things to do. To me, it's much less a question of, "What one thing should I do?" and more, "Which one of the things am I most aligned with doing?"

Jason Jacobs: Awesome. Well I thought this was great. Took us a false start or two and some technical issues, but I'm glad we stuck it out, because you've been a really terrific guest.

Dan Yates: Thanks. And we've demonstrated that even nearing the end of the second decade of the 21st century, it's still actually hard to have a IP-based, highly reliable phone communication, so that's another thing that we've accomplished.

Jason Jacobs: Yeah, well next time, lesson learned. We'll just jump on an emissions-producing airplane, right?

Dan Yates: Exactly. Exactly.

Jason Jacobs: Okay. Dan Yates, thank you for coming on the show.

Dan Yates: Thanks, Jason. It was a pleasure.

Jason Jacobs: Hey, everyone. Jason here. Thanks again for joining me on my climate journey. If you'd like to learn more about the journey, you can visit us at myclimatejourney.co. Note that is .co, not .com. Someday we'll get the .com, but right now .co. You can also find me on Twitter at @jjacobs22, where I would encourage you to share your feedback on the episode or suggestions for future guests you'd like to hear.

Jason Jacobs: And before I let you go, if you enjoyed the show, please share an episode with a friend or consider leaving a review on iTunes. The lawyers made me say that. Thank you.